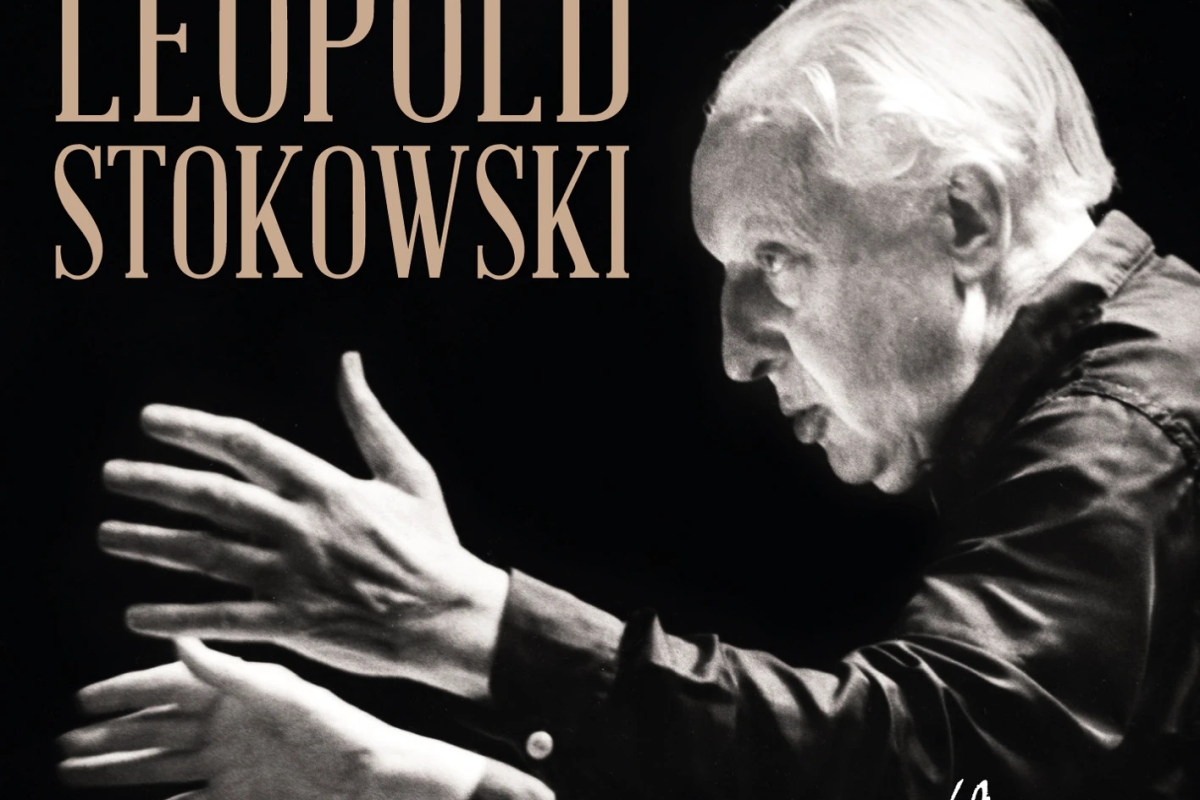

- Leopold Stokowski: A Maestro of Musical Interpretation

- Exploring Stokowski’s Transcription-Encores

- Q&A Section

- Where to buy Loepold Stokowski recordings?

- Want to know more about Leopold Stokowski?

- Listen to Leopold Stokowski FLAC recordings

Leopold Stokowski: A Maestro of Musical Interpretation

Leopold Stokowski, a name synonymous with innovation and controversy in the realm of classical music, left an indelible mark on the orchestral landscape of the 20th century. Revered by some as a magician and master colorist, and criticized by others as whimsical or even charlatan, Stokowski’s approach to conducting was nothing short of singular. His career spanned decades, marked by a relentless pursuit of pushing musical boundaries and eliciting intense, vibrant performances from his orchestras.

Stokowski’s Orchestral Palette

One of Stokowski’s most notable traits was his penchant for interventionist conducting. He was known to deviate from the notated score, implementing wholesale changes in orchestration, cuts, and even re-writing sections of pieces. While this approach garnered both admiration and skepticism, there’s no denying the vividness he brought to music, thrilling audiences with his expressive interpretations and rich orchestral textures.

Unveiling Stokowski’s Late Works

Cala’s dedication to preserving Stokowski’s legacy is evident in their recent releases, showcasing the maestro’s late works recorded in the 1970s. These recordings offer a glimpse into Stokowski’s later years, capturing his enduring passion and vitality despite his advanced age.

Symphony Showcases: Brahms and Mendelssohn

In the recordings of Brahms’ Symphony No.2 and Mendelssohn’s Symphony No.4, Stokowski’s interpretative flair is on full display. While some may note occasional imperfections in ensemble playing, the spontaneity and orchestral blend he achieves are undeniable. Stokowski’s attention to detail and emphasis on phrasing breathe new life into these beloved symphonies, showcasing his unwavering commitment to musical expression.

Schumann’s Symphony No.2: A Stokowski Interpretation

Stokowski’s rendition of Schumann’s Symphony No.2 is marked by moments of brilliance and occasional eccentricity. Despite some mannerisms that may raise eyebrows, his interpretation captures the essence of Schumann’s writing, navigating its complexities with eloquence and depth. From the soaring melodies to the intricate filigree detail, Stokowski’s grasp of the symphony’s design is evident throughout.

Exploring Stokowski’s Transcription-Encores

Stokowski’s penchant for orchestral spectacle is perhaps best exemplified in his transcription-encores. From Debussy’s poetic piano pieces to Shostakovich’s foreboding prelude, each transcription bears Stokowski’s signature flair, offering a unique perspective on these beloved compositions. While some may find his interpretations bombastic or soupy, there’s no denying the sheer audacity and creativity behind Stokowski’s arrangements.

Championing the New and the Familiar:

Stokowski wasn’t just a masterful interpreter of established repertoire; he was a passionate advocate for contemporary music. His recordings of works by Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Prokofiev, like the monumental “Gurre-Lieder” (1932), were groundbreaking at the time and remain valuable historical documents.

However, his interpretations of familiar classics are equally noteworthy. His renditions of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake” (1954) and Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony (1954) showcase his ability to imbue well-known pieces with fresh energy and emotional depth.

The Art of Sonic Sculpting:

Stokowski’s approach to conducting transcended mere baton technique. He meticulously sculpted the sound of his orchestra, employing innovative seating arrangements, experimenting with early recording technology, and emphasizing long, flowing string lines. This approach is evident in his recordings of Debussy’s “La Mer” (1930) and Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain” (from “Fantasia,” 1940), where the orchestra takes on a shimmering, otherworldly quality.

Starting Your Stokowski Journey:

If you’re new to Stokowski, there are several excellent collections to begin with. “The Essential Leopold Stokowski” offers a diverse selection across various composers and periods. For those interested in experiencing the “sonic Stokowski” in all its glory, recordings like “Stokowski: Showpieces” (featuring works like “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”) are a great starting point.

Capturing Tchaikovsky’s Aura

The final CD in Cala’s collection juxtaposes Tchaikovsky’s grandeur with Stokowski’s inventive flair. While Stokowski’s interpretation of Aurora’s Wedding may polarize listeners with its reverberant recording, his skillful conducting brings out the music’s voltage and charisma. Despite the challenges posed by the recording environment, Stokowski’s vision shines through, offering a tantalizing glimpse into his musical world.

Q&A Section

Q1: What defines Stokowski’s approach to conducting?

A1: Stokowski’s approach is characterized by interventionist conducting, often deviating from the notated score to introduce wholesale changes in orchestration and phrasing. His goal was to elicit intense, vibrant performances from his orchestras, pushing the boundaries of traditional interpretation.

Q2: How does Stokowski’s late work differ from his earlier recordings?

A2: In his later years, Stokowski’s passion and vitality remained undiminished, despite his advanced age. His late recordings showcase a continued commitment to musical expression, with a focus on capturing the essence of each composition through innovative orchestral textures and interpretative flair.

Q3: What distinguishes Stokowski’s transcription-encores?

A3: Stokowski’s transcription-encores reflect his penchant for orchestral spectacle, offering bold reinterpretations of familiar compositions. From Debussy’s poetic piano pieces to Tchaikovsky’s grand orchestral scores, each transcription bears Stokowski’s signature flair, showcasing his creativity and audacity as a conductor and arranger.

Where to buy Loepold Stokowski recordings?

On amazon, of course: Buy Leopold Stokowski CDs / LPs / Digital Recordings

Want to know more about Leopold Stokowski?

- Leopold Stokowski on wikipedia EN

- Leopold Stokowski on wikipedia IT

- Biografie – Leopold Stokowski

- Leopold Stokowski | Classical Music, Orchestral …

- Stokowski, Leopold nell’Enciclopedia Treccani

- Leopold Stokowski(1882-1977)

- Leopold Stokowski (1882-1977): “Le mani espressive di …

- Leopold Stokowski